By Donna Francavilla, RTDNA Contributor

You may recall a recent story where a judge determined whether one of Donald Trump’s tweets was considered defamatory. In this article, I reexamine defamation principles originally enacted before the Internet Revolution and ask if they still apply today. Don’t think this was my brilliant idea. I was inspired by a law student’s presentation on the matter at Cumberland School of Law in Birmingham, Alabama. I will share some of her findings along with the observations of her law professor.

It might be worthwhile for journalists to review free speech and defamation principles within the current legal norms in the age of rapid communication. Let’s also take a look at what changes might Donald Trump bring following his campaign promises to change libel laws to make it easier for public figures to sue news organizations.

How it used to be:

When comments of a defamatory nature were published in a newspaper or broadcast on radio or television, the person being defamed had little direct, immediate recourse. Today, with social media, that’s all changed.

What is defamation?

Let’s take look at what defamation is. It arises when a communication harms a person’s reputation, lowering the person’s estimation in the community and involves a “false and derogatory statement that was published to a third person, and the statement causes actual damage.” The two traditional forms of defamation are libel and slander. Libel is a written defamatory statement and slander is a spoken or oral defamatory statement.

Defamation and The Media

Where the defamatory comments are made by the media or where they are directed towards a public figure, the First Amendment requires that the defamed person must prove the offender published a defamatory statement with knowledge that the statement was false or with a reckless disregard of its falsity.

According to a law professor at Cumberland, social media presents additional challenges in determining what is or is not defamatory. “That is especially true when attempting to distinguish between speech that is defamatory and speech that is merely opinion,” says Professor Jill Evans, who teaches the upper level course, Selected Topics in Torts.

A New York judge’s January ruling that Donald Trump’s Twitter assault on a television commentator during the presidential campaign was NOT defamatory is a recent example of how courts are struggling with applying traditional defamation rules to social media. The lawsuit was brought by Cheryl Jacobus, a Republican commentator and political strategist whom Trump branded on Twitter as “a real dummy.” A judge wrote that Trump’s tweets did not qualify as defamatory, even though they were “clearly intended to belittle and demean.”

Sticks and Stones

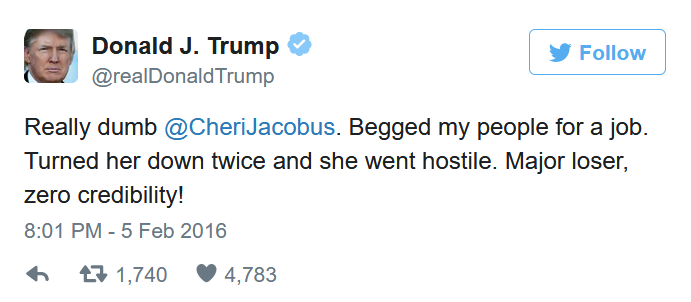

In Jacobus v. Trump, the political strategist filed a libel lawsuit after Mr. Trump on Twitter called Jacobus a “major loser” with “zero credibility” and insisted that she had “begged” him for a job. Here’s a copy of the Trump post:

The Law

The First Amendment requires libel plaintiffs who are public figures, a status Ms. Jacobus certainly held by virtue of her activities during the campaign, to prove actual malice on the part of the defendant. It is unclear how the courts are supposed to determine whether a tweet or Facebook comment is made with actual malice. Professor Evans says that it is the interactive nature of social media that creates some of the difficulty in determining when a statement might meet the actual malice standard. “That is not necessarily a bad thing,” she said. “In some cases the exchange on social media may make it easier to categorize a statement as either non-defamatory or opinion. That is especially so when the statements are directed towards public figures or officials.” That certainly seems to have been the case with Trump’s tweets.

The Ruling

Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Barbara Jaffe asserted that Trump’s speech fell into the category of “hyperbolic” comment in the heat of a political campaign. Jaffe said, “Professional misconduct, incompetence or a lack of integrity may not be reasonably inferred from being turned down from a job.” The court further considered the word “begged” in context with the other negative tweets exchanged between President Trump and Jacobus to establish that the defensive tone of the tweet signaled readers that the two were engaged in a quarrel. President Trump’s characterization that Jacobus “begged” for her job is figurative and loose. Those types of statements, according to the judge, are almost always considered opinions, not facts.

Can the laws be changed?

Law student Taylor Akers is studying defamation and the rise of social media as part of a class looking at trends in tort law. She points out that President Trump has stated a desire to tighten the defamatory libel laws in favor of public figure plaintiffs, although that clearly could have hurt him in the claim by Jacobus. Akers is looking closely at this issue as part of her research. Akers believes that President Trump is facing an uphill battle because libel is a matter of state law and Presidents cannot directly change state laws. According to an article in the New York Times, President Trump would have to either change the First Amendment principles that constrain the country’s libel laws or amend the Constitution itself, neither of which is within the executive powers. Unfortunately for President Trump, until the Supreme Court overrules its landmark decision in New York Times v. Sullivan, public figures still must prove that false statements were made with “actual malice” – a higher bar than that applied to defamation of private citizens.

Akers believes that as the use of social media platforms increase, the lawsuits alleging defamation via social media platforms will continue to increase. She thinks applying existing defamation law to cases involving social media is complicated by the fact that social media differs markedly from traditional forms of media. Social media allows communication about thoughts, emotions and ideas to be delivered to mass audiences instantaneously and without reflection. In fact, the whole purpose of social media is to freely exchange thoughts and ideas but to do so in snippets. Consider Twitter’s 140 character limit on all posts, for example. A speaker has little opportunity to provide context or make it known that his/her post is strictly opinion or hyperbole. Therefore, a court is almost forced to examine the Defendant’s string of tweets and responses to tweets.

Fair Play

According to Professor Evans, social media is also likely to muddy the water with respect to traditional notions of who is considered a public figure for purposes of defamation law. One of the reasons for the higher standard of “actual malice” or reckless disregard when the defamed is a public figure is that they generally had greater access to media and other outlets to respond to any defamatory statements. Akers presentation pointed out that with traditional forms of media, a private individual was less likely to have the resources to combat the defamatory material, hence they must only prove the defendant acted with negligence rather than the higher burden of “actual malice.” Social media gives everyone access to the public.

The First Amendment

While the First Amendment protects the right to anonymous speech, this right is not absolute. Aker says that “where an anonymous speech is thought to be defamatory, the court must balance the speaker’s right to remain anonymous and the Plaintiff’s need to discover the speaker’s identity to establish a claim.” In other words, the court must see evidence that the person being defamed was harmed before it will address the question of whether the speaker will lose his or her anonymity. Akers suspects that the question of what a plaintiff must prove to overcome the right to anonymous speech will play a central role in future cases involving defamation and social media.

What does it all mean?

Listening to this topical presentation as a journalist helped me re-examine the issue. I am convinced that the risk of defamation becomes more prevalent as internet use expands. For now at least, the burden of proof continues to be rather high. One must prove intentional harm and actual malice before a lawsuit can be won. Unlike past United States presidents, Donald Trump says he hates the media, and is threatening to change laws that don’t favor public figures. And THAT could affect the nature of what is said and how it is said.

Possible Easing of the Law toward Public Figures?

Donald Trump pledged to “open up our libel laws” if he became president to make it easier to sue news organizations for unfavorable coverage. Can he actually do it? According to a November 2016 article to the New York Times, the simple answer is yes, but it would be complicated and extremely difficult. Times journalist Sydney Ember said since libel is a matter of state law limited by the principles of the First Amendment, presidents cannot directly change state laws, so Mr. Trump would effectively have to seek to change the First Amendment principles that constrain the country’s libel laws. “There are two potential ways he could do this, according to legal experts. One route is through the Supreme Court. The other is through the Constitution itself.”

Donna Francavilla is an award-winning news reporter in Birmingham, Alabama and owner of Frankly Speaking Communications.